Australia has done relatively well in coping with Covid-19. Our death rate, at the time of posting, of 35 per million puts us 111th out of 201 countries and territories listed on worldometers website. This is well below the world average of 138 deaths per million.

Australia has some obvious advantages. We are an island-continent with a long history of serious quarantine regulations. We pay attention to Asia. We have excellent state capacity. So, that we have done unusually well in coping with Covid-19 is not that surprising.

What is a bit more striking is that, out of 897 deaths from Covid-19, 809 have taken place in the State of Victoria. Victoria is the second-largest Australian State by population, with a population of 6.7m out of Australia’s 25.7m.

There is no mystery about why Victoria (or, more specifically, Melbourne, a metropolis of 5m people) has done so relatively badly. The quarantine of returning travellers in various hotels was screwed up. Very badly. Private security guards were hired to enforce the quarantine. They were not adequately trained or supervised, resulting in a failed quarantine and the spread of the virus.

There has since been a public enquiry into the hotel quarantine failure. The inquiry Judge has not yet released her findings, but the public testimonies by various public servants were, remarkable. A short summary is: no one remembers anything. The decision to use private security guards just sort of happened.

Speaking as an ex-public servant, the parade of not-me and I-don’t-remember testimony was startling. But is perhaps less surprising in the current social context than it might otherwise be.

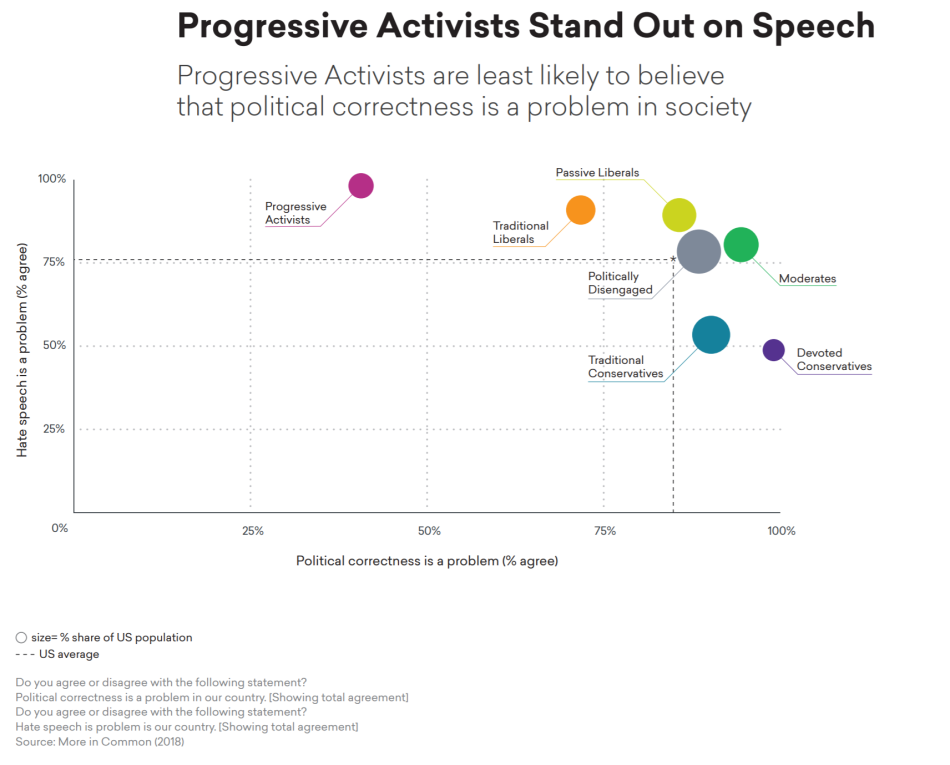

In the Anglosphere particularly, people very much live in a social situation where social media is mobilised to sanction those who express anathematised opinions. Nervousness about expressing opinions has become widespread: a recent poll found that 62% of US residents had opinions they were afraid to express publicly, with a majority of all political groups except “strong liberals” having such opinions. This is congruent with the 2018 Hidden Tribes report which found an overwhelming majority of US residents (80%) thought that political correctness was a problem, with progressive activists (8% of the population) being the only group a majority of whom did not agree that PC was a problem. Progressive activists were generally highly educated, with high socio-economic status and well above average incomes. The sort of people who go into University administrations, non-profit advocacy groups, HR departments and government bureaucracies generally.

In a situation where divergent opinions are socially sanctioned, social safety resides in going along with the preferred opinions. There is a mixture of implicit and explicit social signalling that goes on to establish and maintain an emergent, and evolving, set of approved opinion.

This is not a deliberative process, in the conventional sense. While there are social milieus where future approved opinions are developed, in the wider society it is much more a matter of network processes of feedback and response. People who want to navigate these social risks (and opportunities) need to develop an awareness, not necessarily conscious, of the relevant social cues.

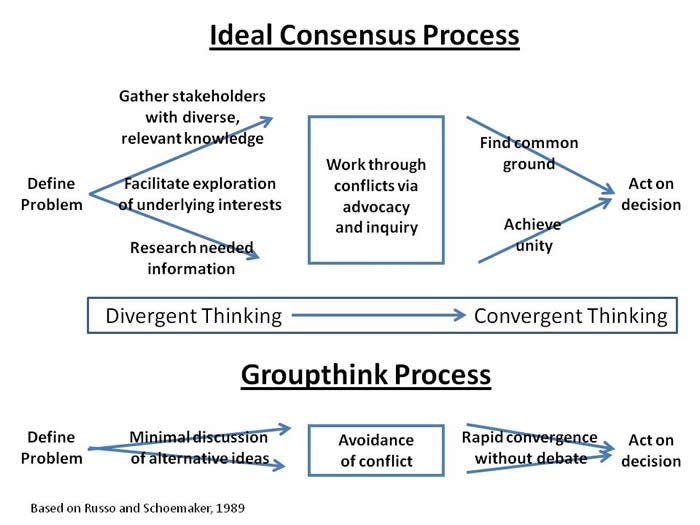

Now, take that process of social signalling and conformity and apply it in bureaucratic settings. It is not hard to see how decisions could end up being made implicitly through mutual signalling rather than explicitly. As an emergent process rather than as explicit decisions.

The trouble with such implicit decision making is that such implicit decisions are not interrogated. Indeed, much of the point is to not interrogate positions, as asking the “wrong” questions can be an adverse social signal. So there is much less thinking through of implications and requirements.

That is how one ends up with a situation where someone involved in the hotel quarantine gets diversity training, as that is an accepted ritual, but no training specific to running a quarantine.

This is brainless decision making, but one that makes perfect social-dynamic sense in a situation where there is systematic sanctioning of anathematised opinions and even asking the wrong questions is socially fraught.

Especially given (1) the dominant intellectual origins of the approved opinions and (2) how useful having a set of approved opinions is for a bureaucracy.

Bureaucratically convenient convergence

Having a set of approved opinions is useful for a bureaucracy, as it simplifies selection procedures, it simplifies coordination and it generates moral projects. A useful, extra and clear sorting device is established for selecting people — are they “one of us? Moreover, if everyone is operating off the same set of opinions, it becomes much easier to align actions and expectations within the bureaucracy. As a third bonus, given that the dominant (dare one say hegemonic?) set of opinions is highly moralised, and all about social action and transformation, it generates moral projects for bureaucracies to be getting along with.

There is also a lot of social science that such cognitive conformity is bad, even disastrous, for decision-making. But that only matters if there are direct consequences to those involved from such decision-making failures. Otherwise, the bureaucratic convenience will win out. Especially if status payoffs are added in, as they are.

The brainless versus the bodiless

The intellectual origins of the dominant approved opinions also reinforce these patterns of emergent, un-interrogated, decision-making. The hegemonic opinions come out of critical social theory (the evolution within the US of critical theory) with its associated constellation of ideas (critical race theory, anti-racism, intersectionality, queer theory, third-wave feminism, fourth-wave feminism).

These ideas have adapted aspects of various French theorists (notably Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard), who themselves were reacting, in the context of the failure of political Marxism, to philosopher Martin Heidegger’s critique of Western philosophy. Three key adaptations into the critical social theory constellation were:

- discourse is self-referential (it only connects to itself),

- society is primarily to be understood as a set of power relations, and

- we live in social bubbles from which we may not be able to escape.

The first is adapted from Derrida, the second from Foucault and the third from Baudrillard.

The significance of these adaptations is clear if we realise that there are four modes of knowledge: propositional, procedural, perspectival and participatory. Knowledge that, knowledge how, knowledge of and knowledge in. Each has its own reality marker: truth, power, presence and (something like) attunement, respectively.

If language, if discourse, only connects to itself, then truth is taken out of consideration as a marker of reality. Propositional knowledge is no longer of knowledge of anything except other propositions. Power then becomes our most effective reality-marker. It thus make sense to conceive of society as a structure of power relations, with speech being acts of power, as critical social theory, and its associated ideas, typically do. With our perspectives and our experience being taken as self-validating and only subject to social validation in terms of power.

Heidegger, Foucault, Derrida and Baudrillard were all very much critics of Enlightenment thinking and leading figures in the development of Post-Enlightenment ideas. Enlightenment thinking concentrated so much on propositional knowledge (Cogito, ergo sum — ‘I think, therefore I am’ — is classic Enlightenment thinking) that it ended up with a thin and bodiless conception of knowledge. One that entirely abandoned wisdom traditions. (Useful discussions of wisdom traditions in the context of cognitive science are here and here.)

Post-Enlightenment abandoning of propositional knowledge as being entirely self-referential creates a situation where people’s speech and actions can only be analysed in terms of power relations, personal perspective and personal experience. If one wanted to be cruel, one would say the Enlightenment versus Post-Enlightenment clash becomes a dispute between the bodiless and the brainless.

The bodiless epistemology of the Enlightenment may have left no place for the wisdom traditions, but the decapitated epistemology of the Post-Enlightenment, deprived of the reality-testing interrogation of truth, has hugely expanded the possibilities for self-deception. Self-deception through accepting what is congenially salient, such as being socially acceptable or otherwise convenient, rather than what is the case, has always been a recurring human foible. Hence wisdom traditions have perennially put much emphasis on self-awareness, on seeking to eliminate self-deception. Denying interrogation of what is the case as a reality marker by treating discourse as an enclosed structure greatly increases the possibility for self-deception, such as through self-deceiving manipulation of moral salience. As we move from Enlightenment to Post-Enlightenment thinking, the retreat from wisdom becomes even more complete.

Decapitating competence

A view that decisions can only be interrogated in terms of power relations is not a view conducive to interrogating them in terms of their practical effectiveness. Practical effectiveness, aka competence, is all about the connection of statements to reality. In the decapitated epistemology of Post-Enlightenment critical social theory, competence gets trumped by caring. Well, by caring in accordance with approved power-relations of marginalisation.

Returning to the testimony to the Victorian hotel quarantine enquiry, the “don’t remember” and “wasn’t me” process of decisions just happening to be made, but not being interrogated, apparently revealed, fits right in. (Especially as the security guards were disproportionately from “marginalised groups”.)

A very powerful social dominance strategy, based on prestige opinions rather than more conventional patterns of prestige goods or prestige skills, has developed in contemporary societies. The status strategy comes in both assertive — look at me, I am so moral — and defensive — I agree, don’t sanction me — versions. The prestige opinions are based around a set of ideas that systematically undermine decision-making competence. The testimony in the hotel quarantine failure inquiry provides a preliminary case study of the effect on decision-making of this prestige-opinions status strategy. A strategy that has to suppress alternatives views and concerns. First, because the moral prestige the social dominance strategy is based around requires claiming that any contradicting ideas be immoral (in the case of these hegemonic opinions, are -ist or -phobe opinions: racist, xenophobic, etc.), so any proponents thereof must be be sanctioned. Second, because otherwise followers of the strategy will be outcompeted by explicit, interrogated, fact-grounded, competent decision-making.

If you want to know what’s in store as sanctioning of wrongthink by power-is-what-matters conformity-by-social-signalling, with its decapitated epistemology, spreads throughout society and its bureaucracies, the un-interrogated decisions that “just emerged” exposed by the testimony to the Victorian hotel quarantine enquiry, and the hundreds of avoidable deaths that conformity-by-social-signalling led to, are a harbinger of things to come. (Coming to a corporate, non-profit or government bureaucracy near you.)

Cross-posted from Medium.

No comments:

Post a Comment