A guest post at Marcus Nunes's blog Historinhas (sans graphs).

In the debate about how to think about the Great Inflation of the 1970s, Milton Friedman's policy advice--constant growth in a targeted monetary aggregate--turned out to be misplaced. Indeed, the failure of the Thatcher Government's monetary aggregate targeting led to the popularisation of Goodhart's Law:

Victory (to a point)

In the debate about how to think about the Great Inflation of the 1970s, Milton Friedman's policy advice--constant growth in a targeted monetary aggregate--turned out to be misplaced. Indeed, the failure of the Thatcher Government's monetary aggregate targeting led to the popularisation of Goodhart's Law:

Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.

Ironically, the point Milton Friedman had originally made (pdf) in his critique of the use of the Phillips Curve for policy purposes--that such a use will change people's expectations, and thus their behaviour, rendering the relationship between inflation and unemployment no longer useful for policy purposes--turned out to also apply to his own policy advice to target monetary aggregates being based, as it was, on the notion that monetary turnover (velocity) was relatively stable (or could be made so by quantitative targeting).

Victory (to a point)

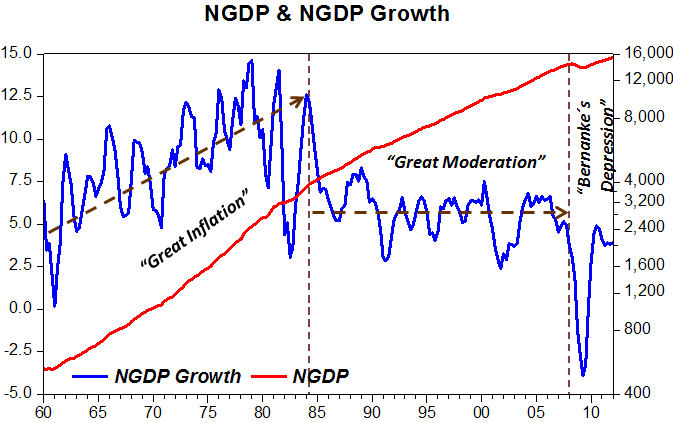

Nevertheless, the wider macroeconomic victory of Milton Friedman--the acceptance that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon--was a necessary step in the taming of inflation. Why? Because once the monetary nature of inflation was accepted, the responsibility of central banks for inflation became clear, incorporated in what is sometimes called the new neoclassical synthesis. So the problem simply became a matter of finding a way to operationalise the responsibility of central banks. Such a way was found with inflation targeting. (Pioneered by, of all places, New Zealand under Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Don Brash.)

In other words, accepting that inflation was a monetary phenomenon gave the central banks no place to hide.

There were two problems which flowed from this. First, what became most widely accepted was narrow inflation targeting, where maintenance of price stability (typically defined as 2% inflation a year) became the only, or dominant, policy target of the central bank.

The second is that, in the wider economics profession, the dominant macroeconomics became New Keynesian economics, where the incorporation of monetarist notions is often glossed over: they do not play much part in David Romer's 1993 paper (pdf), for example. The frequent use of Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) Models, which have some problems incorporating money and monetary effects, rather exacerbated this. Brad DeLong, conversely, makes explicit (pdf) the importance of what he calls Classic Monetarism in New Keynesianism.

Burdensome responsibility

Given the way central banks now pride themselves on--indeed, sometimes seem to define their role as--"taming" inflation, it is easy to forget how resistant many central banks were to the notion that inflation was their responsibility. And a major appeal of narrow inflation targeting is precisely that it minimises the responsibilities of central banks.

Which is why a new (market) monetarist victory is necessary. For the crucial step in flattening the business cycle is to gain acceptance that the intensity of the business cycle is also a monetary phenomenon: that central banks control the level of aggregate demand. Once that is accepted, the responsibility of central banks for stabilising the path of total spending on goods and services is clear, and it is just a matter of finding ways to operationalize that responsibility.

Given Scott Sumner's very reasonable hypothesis that central banks (particularly the US Federal Reserve) tend to follow the macroeconomic consensus of the mainstream economics profession, this means the debate within said profession is very important; though still as part of the wider policy debate.

While central banks are not held accountable for the effects of what they do, and do not do, achieving a stable (macro)economic framework for people to go about the business of their lives is going to be a happy accident when it should be what policy makers—and specifically central bankers—are held accountable for.

ADDENDA: Noah Smith is very enthusiastic about Japanese PM Shinzo Abe because, among other reasons:

[Cross-posted at Skepticlawyer.]

In other words, accepting that inflation was a monetary phenomenon gave the central banks no place to hide.

There were two problems which flowed from this. First, what became most widely accepted was narrow inflation targeting, where maintenance of price stability (typically defined as 2% inflation a year) became the only, or dominant, policy target of the central bank.

The second is that, in the wider economics profession, the dominant macroeconomics became New Keynesian economics, where the incorporation of monetarist notions is often glossed over: they do not play much part in David Romer's 1993 paper (pdf), for example. The frequent use of Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) Models, which have some problems incorporating money and monetary effects, rather exacerbated this. Brad DeLong, conversely, makes explicit (pdf) the importance of what he calls Classic Monetarism in New Keynesianism.

Burdensome responsibility

Given the way central banks now pride themselves on--indeed, sometimes seem to define their role as--"taming" inflation, it is easy to forget how resistant many central banks were to the notion that inflation was their responsibility. And a major appeal of narrow inflation targeting is precisely that it minimises the responsibilities of central banks.

Which is why a new (market) monetarist victory is necessary. For the crucial step in flattening the business cycle is to gain acceptance that the intensity of the business cycle is also a monetary phenomenon: that central banks control the level of aggregate demand. Once that is accepted, the responsibility of central banks for stabilising the path of total spending on goods and services is clear, and it is just a matter of finding ways to operationalize that responsibility.

Given Scott Sumner's very reasonable hypothesis that central banks (particularly the US Federal Reserve) tend to follow the macroeconomic consensus of the mainstream economics profession, this means the debate within said profession is very important; though still as part of the wider policy debate.

While central banks are not held accountable for the effects of what they do, and do not do, achieving a stable (macro)economic framework for people to go about the business of their lives is going to be a happy accident when it should be what policy makers—and specifically central bankers—are held accountable for.

ADDENDA: Noah Smith is very enthusiastic about Japanese PM Shinzo Abe because, among other reasons:

In other words, unlike everyone else in the world, Abe listened to Milton Friedman, and the results are looking good.

[Cross-posted at Skepticlawyer.]

No comments:

Post a Comment