People have a pretty good understanding of their own continental ancestry. People are also relatively accurate at picking out other people’s continental ancestry.

This is not surprising. There was not much mixing of lineages across continents until relatively recently, at least outside continental border regions. This was due to the limitations of technology: specifically very limited transport capacitie. Moreover, thousands of years of separate genetic lineages, with genetic bottlenecks creating relatively small founder populations for various continents, meant that there are fuzzy-boundary, but relatively clear, patterns of physical markers of continental ancestry.

So, a folk concept of race based on continental ancestry has some, relatively straightforward, patterns of physical-markers to work off. Hence the history of skin-tone descriptors of race. With race becoming to be understood as being continental, or some significant sub-continental region, ancestry. (Medieval Europeans had a rather different concept of race, one much more language based — so it made sense for a C14th commentator to talk of Scotland being one nation with two races: highlanders and lowlanders as thy spoke different languages.)

The US in particular has a long history of obsessing over race because continental origin coincided with fundamentally different roles in colonial society (the settlers, the dispossessed and the enslaved). Different roles that persisted into the country created by the American Revolution.

Slavery, settlement and racism

As continents produce neither single cultures per continent nor single breeding populations per continent, analytically, remarkably little follows from physical markers of continental ancestry being relatively clear. But as physical markers of continental ancestry are collectively visually relatively clear, they can, very easily, have social meanings attached to them. Which, of course, has happened repeatedly. Especially when one region has systematically enslaved people from region(s) with different general patterns of physical markers. Or when folk from one continent have populated another. We can call these the slavery effect and the settlement effect.

Both have proved to be powerful generators of racism: attaching normative ranking to continental (or region thereof) origin. That is, positive social meaning to one’s own group and (especially) pejorative social meaning to those with a different continental origin (and so a different social role).

A third generator of racism has been imperialism: domination of a state created by one continental origin group over folk with differing continental origins. This has been a rather stronger generator of elite or theoretical racism than more general racism, as imperialism is mostly an elite activity. (A 2018 study found that the UK and Portugal, the two surveyed countries with the longest histories of colonialism, had generally the lowest levels of racism among the surveyed European countries.) Though all racism, and race talk, starts off as an elite discourse.

The fourth generator of racism has been ethnicised religion. The classic version of this being racialised Jew-hatred.

None of these factors are sufficient in themselves to generate racism. The Romans were mass-enslaving imperialists who settled new areas and tended to dislike Jews. Racism was not a feature of their culture.

For the Romans were not a xenophobic culture regarding descent. Folk of any origin could become Roman citizens, including ex-slaves. Their slaves could be of any origin. Their society and their thought did not structurally differentiate by continental origin.

Moreover, Romans traditionally were not moral universalists. So, they did not have to generate some generalised story about why some folk were slaves. Slaves were simply losers and if they were freed, and became Roman citizens, then they became winners. Folk would put that they were freedmen (i.e., ex-slaves) on their tombstones, as that showed how much of a winner they had become.

Islam and racism

The first significant discourse grading people as cognitively deficient, based on physical markers of continental origin, came out of Islam. Islam being an imperial, evangelising monotheist (so morally universalist) religious civilisation that systematically enslaved people to their north (including Europeans, notably Slavs) and people to their south (Sub-Saharan Africans).

Folk of such origins were repeatedly characterised by Islamic writers as being cognitively deficient. Often either due to too little sun (Northern Europeans) or too much sun (Sub-Saharan Africans). So, in Chapter Three of his Tabaqāt al-ʼUmam (Categories of Nations), geographer Sa’id al-Andalusi (1029–1070) wrote:

The rest of this category, which showed no interest in science, resembles animals more than human beings. Those among them who live in the extreme North, between the last of the seven regions and the end of the populated world to the north, suffered from being too far from the sun; their air is cold and their skies are cloudy. As a result, their temperament is cool and their behaviour is rude. Consequently, their bodies become enormous, their colour turned white, and their hair drooped down. They have lost keenness of understanding and sharpness of perception. They were overcome by ignorance, and laziness, and infested by fatigue and stupidity. Such are the Slavonians, Bulgarians and neighbouring peoples.(The English word slave likely derives from Slav.)

The patterns of castrating male slaves, and of incorporating the children of Muslim fathers into the umma, the Muslim community, meant that centuries of mass slavery failed to generate an ex-slave underclass within Islamic lands. But there are still linguistic traces of these centuries of mass slaving: abd in Arabic can both refer to slave (as in Abdullah, slave of Allah) and to Sub-Saharan African.

Christianity and racism

The Americas were subject to imperialism and mass settlement from Christian Europe. Added to this imperialism and settlement, millions of slaves were imported from Africa. This made continental origins socially salient in the Americas and did so from within a morally universalising religious perspective Christianity). This was a situation made for racism to develop. Which it duly did.

Hence the confused interaction between Christianity and racism. On one hand, the Gospel of Love applies to everyone. Indeed, from the earliest days of Christian European settlement of the Americas, there were devout Christians who spoke and agitated on behalf of the moral status of the inhabitants of the Americas as children of God.

An early, and important, manifestation of this was the 1537 Papal Encyclical Sublimus Dei declaring that the inhabitants of the discovered lands, even if they did not know Christ, were children of God with natural rights and could not be enslaved. In the words of Pope Paul III:

… the said Indians and all other people who may later be discovered by Christians, are by no means to be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property, even though they be outside the faith of Jesus Christ; and that they may and should, freely and legitimately, enjoy their liberty and the possession of their property; nor should they be in any way enslaved; should the contrary happen, it shall be null and have no effect.This did not bar owning slaves someone else had enslaved. As African rulers were more than happy to take care of that stage of the process, Sublimus Dei had little effect on the Atlantic slave trade.

The Anglosphere abolitionist movement in the C18th and C19th had strong Christian roots. As did the US civil rights movement of the mid C20th.

On the other hand, Christianity is a morally universalist religion. Like Islam, it required some justifying story about why you were systematically enslaving the children of God from Africa. It required some justifying story about why you were dispossessing the children of God in the Americas.

Enlightenment thought, which was also morally universalising, had much the same confused interaction with race and racism as Christianity. On one hand, the scientific impulse to categorise could be, and was, mobilised to propagate racist ideas. On the other hand, seeing the world as a shared globe inhabited by a single human species, along with a sense of expanding human capacities, made slavery morally problematic on a scale never seen before. Hence the rise of the abolitionist movements.

As for the settlement effect, so long as the Amerindians were being dispossessed (and feared) by the settlers from Europe, the structural reasons to be racist against them remained strong. After they were subjugated and shoved into reserves, the underlying structural motives to be racist against them lost strength. The effortless virtue, and pleasures of contempt, that bigotry provides may linger, but the general social retreat from, and anathematising, of racism has further weakened what was already a form of racism in structural retreat. As the eminent political career of Herbert Hoover’s Amerindian Vice President, Charles Curtis, demonstrated.

The intensities of slavery

Slavery and its aftermath proved to be a different matter to self-justifying antipathy to Amerindians, who always had a certain warrior vigour going for them. As sociologist Orlando Paterson has brilliantly analysed, slavery does much more then reduce people to property, it imposes on the slave a form of social death. They have no social standing, no family standing nor heritage to be acknowledged. Slavery is profoundly stigmatising and dishonouring, as it deprives the slave of the capacity to have honour or any status that casts doubt on being a slave.

The slave States of the US operated one of the most closed slave systems in history. It became legally hard to manumit a slave and the stigmatising dishonour of slavery was not excised by freedom. A process of stigmatisation greatly helped by the slaves being of a different continental origin than the settlers. The generalised theories that justified slavery could not allow space for some moral transformation from not being a slave anymore.

Roman slavery, not having that justificatory burden, and not being divided by continental ancestry, was far more open. Hence ex-slaves could become citizens and would even boast of how far they had come from their former slave status.

In much of the Americas, an intermediary mulatto or mixed race (i.e. mixed continental origins) identity grew up. Such folk served useful intermediary roles between a small settler elite and large slave or indigenous population. This did not happen in the slave South of the US, as the political importance of voting, and the scale of European settlement, worked against a mixed-race identity emerging.

There was no particularly useful social role that a mixed-race group could fulfil that was not already being filled by folk of European ancestry. Moreover, if ex-slaves and their descendants began voting in any numbers, they could begin to wield political power. Which was both politically threatening and an affront to the justifications for slavery. The result was the “one-drop” rule, whereby any African ancestry identified your slave origins, with all the associated stigmas and exclusions.

These structures served the divide-and-dominate politics of the plantation elite. Before the Civil War, the plantation elite used a range of mechanisms to repress poor “whites”, the masterless men, who had no stake in the slave system but who traded and socialised with the slaves. After the Civil War, and the failure of Reconstruction, the plantation elite used the same range of mechanisms to repress the ex-slaves and their descendants. They simply racialised the operation of exactly the same repressive mechanisms that had operated against the masterless men before the Civil War into what became known as Jim Crow. The former masterless men were now on the “right” side of the exclusions, and were thereby incorporated into the Southern system.

As African-Americans migrated to the industrialising cities, a version of such divide-and-dominate strategies turned out to be congenial to, and adaptable by, urban elites. Public policy was wielded to generate increasing residential segregation, as such segregation makes divide-and-dominate tactics far more effective.

A note in Richard Rothstein’s revelatory The Color of Law, sets out the path of residential segregation. Residential segregation that was driven by public policy. Including intensifying under FDR’s New Deal. In the ten largest US cities:

…in 1880, the neighborhood (block) on which the typical African-American lived was only 15 percent black; by 1910 it was 30 percent, and by 1930, even after the Great Migration, it was still only about 60 percent black. By 1940 the local neighborhood where the typical African-American lived was 75 percent black.At all stages, such divide-and-dominate politics only worked because people bought into the political framings and discourses that legitimated them. Far more of our thinking and decision-making is unconscious than we realise. Social selection processes work on information and feedback: but not necessarily fully conscious, or sufficiently critically examined, information and feedback.

Weakening racism

The experience of the Second World War, both the mass mobilisation for a common purpose and the horrors of Nazi imperialism and racism, as well as the pressures of the Cold War, increased, both domestically and internationally, the embarrassment that American racism generated. At the same time, the continuing fail in transport and communication costs made it easier for marginal groups to organise, as did increased urbanisation and suburbanisation.

So, the structural supports for divide-and-dominate racism weakened. The civil rights movement, and particularly Martin Luther King, brilliantly played up the moral embarrassment of racial exclusion. Both the Christian moral embarrassment and the American-ideals moral embarrassment. With mass communications making it easier to reach people for persuasive effect.

Hence the successes of the civil rights movement and the retreat of racism from being pervasive within American society to being a moral shame. Though, as Glenn Loury makes clear in The Anatomy of Racial Inequality, complex patterns of stigma have been rather more stubbornly persistent.

From this history, we can see that structural racism (or analogues such as systemic racism) is generally not a useful term. For it has been far more the case that structures generate and mobilise racism than that racism generates structures. Nor are such structures a necessary part of the social system. They are more about bending the social system in a particular direction.

After the civil rights movement

Which brings us to the graph at the top of this post and its odd pattern whereby “white” (i.e. Euro-American) Democrats were very much more likely to say that they knew someone who was racist in 2015 than in 2006, but “black” (African-American) and Hispanic Democrats were apparently somewhat less likely to say they knew someone who was racist in 2015 than in 2006.

If someone knows more people they regard as racist than someone else, that can be because (1) they are more likely to meet racists; (2) they are better at identifying racism; (3) they are more expansive in their characterising of racism; or (4) some combination thereof.

So, taking the 2006 results in the graph above, it could be that Euro-American Democrats were more likely to meet racists than Hispanic Democrats or Euro-American Republicans. Or that they are better at identifying them than Hispanic Democrats and Euro-American Republicans. Or that they have a more expansive definition of racism than do Hispanic Democrats and Euro-American Republicans. Or some combination of the above.

If we move to the 2015 results, Euro-American Democrats were far more likely to believe they knew a racist than were African-American Democrats, Hispanic Democrats or Euro-American Republicans. They were also the only group who increased their likelihood of knowing a racist since 2006, and did so dramatically. By contrast, both African-American Democrats and Hispanic Democrats became, if anything, less likely to believe they knew a racist. (The shifts were not statistically significant but do accord with long term patterns of declining racism.)

The most plausible read of this data is that racism has declined somewhat in the US (in accordance with long-term trends) but Euro-American Democrats have acquired dramatically more expansive definition(s) of racism. (Unless they are registering dramatically increased anti-white racism — we can reasonably give that low probability.)

So, by 2015, Euro-American Democrats apparently lived in a US of significantly more racists among the people they interacted with, while African-American Democrats and Hispanic Democrats did not.

If fluctuations in racism are largely driven by changes in structural factors, as history strongly suggests, that suggests a change in structural factors that is particularly affecting Euro-American Democrats, but not other folk. Something that is making race much more salient to them.

An obvious factor is the massive increase, since around 2010, in the use of racial terms by US elite media. As Democrats have far more confidence in elite media than do Republicans (a long-term tendency that increased dramatically from 2015), the dramatic upsurge in the media’s use of racial terms could be accounting for much of the “more people know a racist” effect.

Especially as there clearly has been an expansion of what counts, within elite race talk, as racism. Partly because our concept of a phenomena tends to expand as the prevalence of that phenomena shrinks. There has been, for example, a creeping expansion of what is labelled as harm in Psychology. But there has also been an expansion of the concept of racism due to the expanding influence of intersectionality and critical race theory. Especially in the education of increasing numbers of younger journalists.

Is there a structural reason for this increased focus on race? One is fairly obvious: the value of anti-racism as a status play. The more intense one’s opposition to racism, the greater the moral prestige in being ostentatiously anti-racist and, conversely, the greater the moral shame from failing to appropriately oppose racism. So, a status-play purity spiral gets set up. One that can be used to lever folk out of jobs. The bottom-up (but still elite) prestige play then becomes a dominance play. In a situation of elite over-production, such status-plays are a very useful weapon in struggles over opportunities and resources.

Ostentatious anti-racism can make one reluctant to admit that racism has declined or to give credence to other factors in explaining social dynamics. One becomes invested in continuing to ascribe social meanings to race. The surge in hate crime hoaxes fits in with this.

Function does not require intent

Unconscious psychological processes outstrip conscious reasoning, both in time and in scope, which makes many psychological phenomena possible…

Andrew M. Lobaczewski, Political Ponerolology: A Science on the Nature of Evil Adjusted for Political Purposes, p.163.The other reason for increased focus on race is less obvious, but has a longer historical pedigree. Overt racism might have become embarrassing, but the advantages to urban elites of divide-and-dominate politics has never gone away, so social selection pressures will continue to favour such politics. The more divided residents, workers and citizens are on racial grounds, the less elites have to deal with competing (against them) claims on resources. Symbolic race-identity politics are way cheaper for elites than politics that delivers good government. That is as true today in urban US as it was in the Antebellum or Jim Crow South. Hence racially-divided US cities are (by developed democracy standards) comparatively ill-governed, just as the Antebellum and Jim Crow South were in their time.

If anti-racism can be turned into a racialised divide-and-dominate strategy, as clearly it can, then all the better for opportunity-hoarding elites. Especially for elites facing intensified internal competition for resources and opportunities.

Intersectionality and critical race theory are very much elite products, coming out of places such as Harvard Law School. Nor do they have to be originally developed as divide-and-dominate mechanisms for social selection pressures to adapt them into divide-and-dominate mechanisms.

Moral concern easily becomes status plays. Status plays are naturally divisive. Moral dominion easily becomes social dominion. Such feedback loops provide much for social selection processes to work on.

Such outlooks and patterns of action do not have appear to their active proponents to be divide-and-dominate politics in order to function as such. Remembering that such framings and discourses work much better if folk can be convinced to go along with them, while social selection processes do not have to be entirely conscious. Especially as the prime mechanisms for self-deception are by manipulating salience. Particularly moral salience.

One cannot force oneself to believe what one doesn’t believe. We can, however, use focus on, for example, image-self-protection, to block paying attention to awkward facts or considerations. This is especially easy to do with highly moralised concerns and self-images. Both because of their emotional power and because it is inherent in moral claims that they be normative trumps. That one has an ostentatious image of oneself as being not-oppressive does not guarantee that one is not buying into politics that are, in fact, oppressive or self-serving.

Coverage by elite media of deaths in police custody, or at the hands of police, is particularly revealing. There is a general problem of police training and accountability in the US. One that varies far more by jurisdiction than it does by race (whether of police or civilian protagonist). If media had reported these things accurately, then a broad coalition could have been built up to improve police training and accountability.

Instead, by intensely and selectively racialising their coverage, the “racist cops” narrative was firmly established by elite media. Turning this into a specifically African-American-and-police problem rather than a general accountability-to-the-citizenry problem and allowing those propagating, and those accepting, the narrative to thereby parade their ostentatious anti-racism. A way easier, and more immediate, social and cognitive reward than doing the hard work of increasing police training and accountability. Hence “defund the police”: a simplistic but convenient symbolic politics that was way easier to pander to than improved police training and accountability.

Revitalising divide-and-dominate

The “racist cops” media narrative, and activism, so congenial to moralised self-image, and their associated status plays, has increased the level of violence in those localities and so increased the most racially divisive element in US cities. If one was seeking to revitalise divide-and-dominate politics, it would be hard to do better.

A recent study found that the more educated you were, the more politically progressive you were, and the more you trusted the media, the less well informed you were on police shootings. (But the more conveniently you believed, as far as divide-and-dominate politics went.)

Social intent does not entail social function. Social function does not entail social intent.

Elite race talk is always a divide-and-dominate mechanism. Elite race talk has, historically, been racist. Indeed, racist discourses have always started off as elite theories. But anti-racist race talk works just as well as a divide-and-dominate mechanism, provided one continues to ascribe social meanings to race and do so in pejorative ways. Which, of course, is what all the talk about whiteness, white supremacy, white racism, etc. does.

It is still a case of structures generating the assigning of divisive social meanings to race, far more than the reverse, seeking to bend the social system to their benefit. Even doing so within ostentatiously anti-racist rhetoric and moral framings.

What is that French saying? plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing …

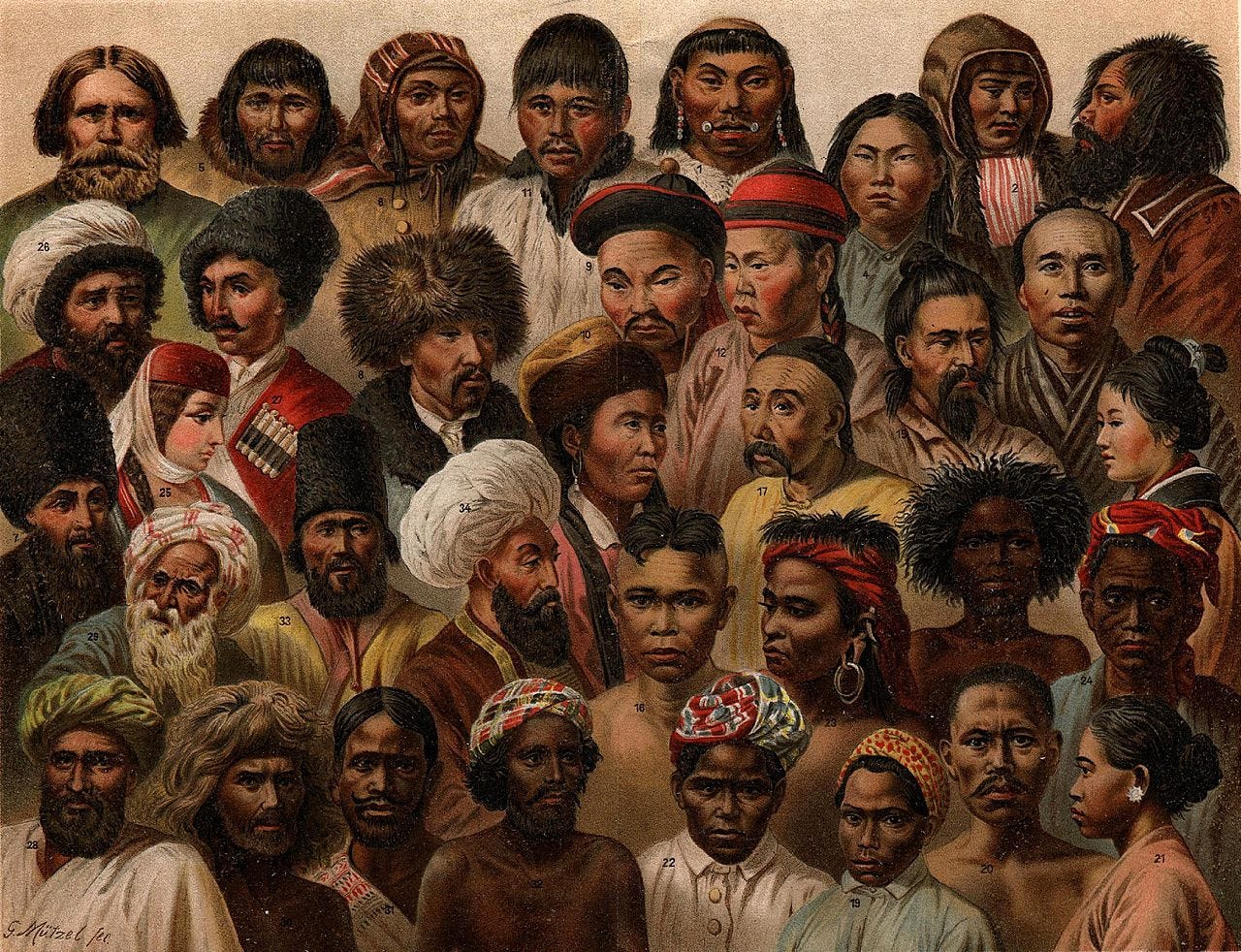

A 1904 depiction of Asian ethnicities.

A 1904 depiction of Asian ethnicities.