Four great out-of population expansions have widely dispersed Homo sapien populations. The out-of-Africa expansion of foragers; the out-of-the-river-valley expansion of farmers; the out-of-the-steppe expansion of pastoralists; and the out-of-Europe expansion of settler empires and states.

Out of Africa: the expansion of Homo sapiens

Whether an exit from Africa around 100,000 years ago was successful or not is still debated. From around 60-50,000 years ago, there was a sustained exit from Africa. Homo sapiens spread to occupy all continents except Antarctica, absorbing and replacing all other Homo populations. These foragers spread at a rate of about 10km a year, at least in areas without existing Homo populations.(1)

Homo sapiens are more gracile than other Homo, so likely lower in reactive aggression and thus more cooperative. Though the delay in the exit(s) from Africa, and the long period of coterminous occupation of Eurasia (maybe 20,000 years), suggest only a marginal advantage over Neanderthals, although this may have changed over time. This spreading of Homo sapien foragers concluded with the settling of southern regions of South America around 14,600 years ago.

Out of the river valleys: the expansion of farmers

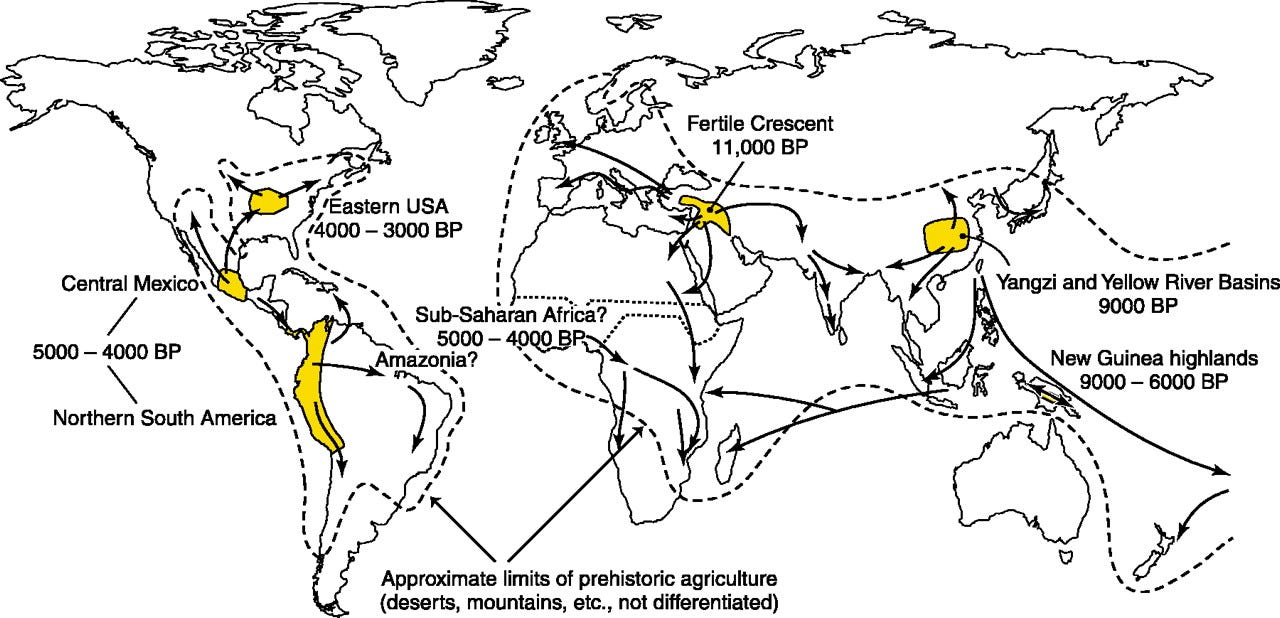

Starting around 11,000 years ago, farming populations expanded across arable land, absorbing and replacing foragers. The process is still going on in Africa, Amazonia and elsewhere. In Oceania, farmers occupied islands without previous human habitation, reaching New Zealand probably around the year 1320.

The transmission from foraging to farming was a lengthy one. While not generally more productive per hour of effort than foraging, farming was able to extract many times more calories from arable land, lowered the cost of child-rearing and created an increased protection problem, encouraging the development of more coercive capacity.(2) Hence the continuing expansion, and dispersal, of farming populations.(3) Farmers and farming generally spread across arable land at a rate of around 1km a year.(4) The development of farming also had significant adverse health consequences, with deteriorations in dental health, loss of height, increased infectious disease and more signs of metabolic stress.(5)

Farmers seem to have traded-off less food-search time (food search being more difficult for child-minding) for more food-processing time (easier for child-minding) and more immediate access to energy (calories) (so quicker weaning of children) for less long-term access to nutrients.

With the development of farming and pastoralism, there was a dramatic narrowing in male genetic lineages. The rate of elimination of male lineages varied by region. Overall, only about 1-in-17 male lineages survived this harrowing of male lineages. (Female lineages were almost entirely unaffected.)(6) This harrowing of male lineages was a result of the expansion among agro-pastoral peoples of the (social) technology of aggression against fellow humans.

The development of pastoralism intensified the pattern of elimination of male lineages.(7) The harrowing of male lineages largely came to an end with the development of chiefdoms and states. That is, when the technology of exploitation overtook the technology of aggression — conquered males became providers of tribute and taxes, so were worth protecting.

Out of the steppes: the Indo-European pastoralist expansion

Pastoralist populations from the Pontic-Caspian steppe domesticated the horse (though the Botai people further east may have domesticated horses earlier) and, from about 5,000ya, and continuing until about 3,000ya, expanded into Europe, the Iranian plateau, the Tarim Basin and Northern India. During these surges of settlement, Indo-Iranians develop the horse-drawn chariot (c.4,000ya).

The steppe-descended pastoralist population eventually expanded across all of Europe, interbreeding with the Neolithic farmers. Though not in the Basque Country and Sardinia.(8)

The original steppe pastoralist population had, like various other pastoralist populations have, developed a mutation for lactase persistence. This enabled much higher metabolic return from post-infancy consumption of milk. Different pastoralist populations in Afro-Eurasia have developed different lactase persistence mutations.(9)

Dairying broadens access to nutrients and enables the extraction of around five times as much calories from grassland as could be done via ruminant meat consumption.(10) This biological advantage likely enabled millennia of expansion, resulting in Indo-European languages, and cultural patterns ultimately derived from steppe pastoralism, covering Europe, the Iranian plateau and Northern India.

After the Indo-Europeans settlement surges had petered out, Indo-Iranian peoples also pioneered horse archers and heavy lancers (c.2,700ya). Later pastoralist peoples continued to periodically ravage, or even conquer, agrarian peoples. Only the Arab and Turkic dispersals resulted in large-scale demographic expansion beyond pastoralist heartlands. In both cases, settlement following imperial conquest.

Out of Europe: the empires-and-settlers expansion

Beginning c.1500 and petering out c.1960, European populations expanded across Siberia, the Americas and the Antipodes.

The combination of competitive jurisdictions, single-spouse marriage, the abolition of kin groups (requiring the development of replacement mechanisms of social cooperation), as well as being able to entrench social and political bargains in law (as law was not based in revelation, unlike Sharia and Brahmin law) meant that Europe had far more variety of political institutions than elsewhere. This gave the selection processes of history far more to work with, resulting in Europe developing more effective states. Christian Europe’s swift adoption of the printing press after 1450 greatly aided the dissemination and development of information and technology while reducing administrative costs.

With gunpowder, the compass, and ocean-going sail technology, Europeans spread out from Europe in a largely maritime out-of expansion. The out-of-Europe expansion included waves of settlement. (The Russian conquest and settling of Siberia did not need the maritime step, though riverine expansion was important in parts of Siberia.)

Settlement generally followed, sometimes preceded, imperial expansion. Both the Russian and American nation-building-through-settlement were also imperial projects, although animated by rather different ideas and institutions.

The Europeans acquired a portmanteau biota of supporting plant and animal species. Where their portmanteau biota became dominant, Europeans became the dominant human population, creating neo-Europes. Where the biota failed to do so, they did not.(11)

Being Eurasian, so resistant to the Eurasian disease pool, gave Europeans a disease advantage in the Americas and the Antipodes. Having much more effective states was their advantage within Afro-Eurasia and allowed them to exploit their disease advantage far more completely and speedily outside it. Their advantage in state (and other cooperative) organisation eventually (albeit temporarily) expanded their control across regions where they were systematically disease-disadvantaged (including Sub-Saharan Africa).

The Homo sapien advantage is non-kin cooperation. Medieval European Christian civilisation put non-kin cooperation “on steroids” and so Europeans equipped with compass, gunpowder, ocean-going maritime technology and the printing press created the Eurosphere across four continents plus Siberia and ended up dominating the planet — until other peoples learnt their tricks.

In general

The expansions have been getting faster: taking at least 35,000 years; 11,000 years; 2,000 years; 500 years.

The, currently underway, fifth great out-of expansion — the out-of-the-countryside movement to the cities — is a series of concentrations, rather than a dispersal.

Each of the out-of dispersals has its specific characteristics, but each represents Homo sapiens behaving like Homo sapiens. Indeed, behaving like any biological population with access to new resources, including new abilities to access resources.

Endnotes

- B. Llamas, L. Fehren-Schmitz, G. Valverde, J. Soubrier, S. Mallick, N. Rohland, S. Nordenfelt, C. Valdiosera, S. M. Richards, A. Rohrlach, M. I. B. Romero, I. F. Espinoza, E. T. Cagigao, L. W. Jiménez, K. Makowski, I. S. L. Reyna, J. M. Lory, J. A. B. Torrez, M. A. Rivera, R. L. Burger, M. C. Ceruti, J. Reinhard, R. S. Wells, G. Politis, C. M. Santoro, V. G. Standen, C. Smith, D. Reich, S. Y. W. Ho, A. Cooper, W. Haak, ‘Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the America’s,’ Science Advances, April 2016, Vol.2, №4, e1501385, suggests that it took 1.4kya to people the length of the Americas. As this is a distance of roughly 14,000km, that is an expansion rate of around 10km a year.

- Samuel Bowles, ‘Cultivation of cereals by the first farmers was not more productive than foraging,’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 2011, 108 (12) 4760–4765.

- Jared Diamond, Peter Bellwood, ‘Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions,’ Science, 25 April 2003, Vol. 300, Issue 5619, pp. 597–603.

- Joaquin Fort, ‘Demic and cultural diffusion propagated the Neolithic transition across different regions of Europe,’ Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2015, 12: 20150166.

- Katherine J. Latham, ‘Human Health and the Neolithic Revolution: an Overview of Impacts of the Agricultural Transition on Oral Health, Epidemiology, and the Human Body,’ Nebraska Anthropologist, 2013, 187.

- Tian Chen Zeng, Alan K. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 9 Article number: 2077 (2018), published 25 May 2018.

- Patricia Balaresque, Nicolas Poulet, Sylvain Cussat-Blanc, Patrice Gerard, Lluis Quintana-Murci, Evelyne Heyer & Mark A. Jobling, ‘Y-chromosome descent clusters and male differential reproductive success: Young lineage expansions dominate Asian pastoral nomadic populations,’ European Journal of Human Genetics, January 2015.

- Iosif Lazaridis, ‘The evolutionary history of human populations in Europe,’ arXiv 1805.01579, submitted on 4 May 2018.

- Hadi Charati, Min-Sheng Peng, Wei Chen, Xing-Yan Yang, Roghayeh Jabbari Ori, Mohsen Aghajanpour-Mir, Ali Esmailizadeh and Ya-Ping Zhang, ‘The evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence in seven ethnic groups across the Iranian plateau,’ Human Genomics, (2019) 13:7. Scholarly discussions of lactase persistence in Europe often pay remarkably little attention to the same specific lactase-persistence mutation occurring in Europe, Iran and Northern India, so must have spread by a pastoralist, not a farming, population.

- Latham, op cit. Morton O. Cooper and W. J. Spillman, ‘Human Food from an Acre of Staple Farm Products,’ Farmers’ Bulletin, №877, October 1917, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending, The 10,000 year explosion: how civilization accelerated human evolution, Basic Books [2009] (2010) cite the Bulletin for their discussion in Chapter 6 of the Indo-European expansion, including the role of lactase persistence.

- Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900, Cambridge University Press, [1986] (1993).