Patriarchy is authority being presumptively male. The more presumptively male authority is, the more patriarchal the society is. At its simplest, authority is competence + deference. The wider and more significant the realm of presumed male competence, and of expected deference to the same, the more presumptively male authority is.

That an area of life is presumptively male does not, of itself, generate patriarchy. Having presumptive sex roles is not patriarchal. The addition of expected deference is crucial. For without such expected deference, there is no authority, just things folk generally do.

To understand patriarchy, we need to start with the basics of sex and gender.

Sex

Sex is determined by what gametes your body is structured to produce. If it is structured to produce small, self-moving (motile) gametes you are male. If it is structured to produce large, sessile (immobile) gametes, you are female. This is so whether or not viable gametes are produced.

If your body is structured to produce both, you are both male and female. If your body is structured to produce neither, you are neuter. (As distinct from being deliberately stripped of the ability to produce gametes, which is being neutered.)

If your body has elements of both male and female sexual structuring, then your sex can be somewhat indeterminate (i.e., intersex), but normally your body will favour one type of structuring over the other. Such mixed cases do not mean that sex is not binary. It just means that a (very small) proportion of folk do not have bodies that are entirely on one side of the border between sex-typical biological structures.

[Sex is binary at the level of reproductive function, due to there being only two gametes, but, in humans, is bimodal rather than binary at the level of bodies.]

We cannot do sex-reassignment or sex-change surgery. We cannot shift the structuring of your body to produce different gametes. We can only do gender-reassignment surgery that changes the visible physical manifestations of biological sex. Hence hormonal supplements are needed by trans folk, as we cannot change your body to change the pattern of hormones it produces.

Children

Homo sapiens are mammals. Female mammals have mammary glands so that when the child emerges, their immediate food source is on-tap.

In most mammal species, that means the male plays no role in raising children, as the female is already committed (via the mammary glands) to feeding the children. This is the cad strategy for reproduction. The more the children have to be taught how to feed, and the longer they have to be fed before they can feed themselves, the more likely some male involvement in the feeding of the offspring is (the dad strategy).

Male provision is not to be confused with mate-guarding. Mate-guarding is about taking possession of the fertility of a female for one’s own use, excluding other males. It implies nothing regarding the care of children. Most mate-guarding mammal species have cad-strategy males. They are just possessive cads.

In contemporary foraging societies, on average, children do not “break even” in producing and consuming calories until about the age of 20. So, a Homo sapien child, on average, has likely represented about a 20 year-feeding-protection-and-instruction investment. This was not possible without provisioning males.

In contemporary foraging societies, men provide a majority of calories to the group, an overwhelming majority of the protein to the group and almost completely dominate provision of calories and protein consumed by post-weaning children. The only evolutionary stable way to get males to invest that much effort in provisioning children is having them feed the children that are presumptively theirs. That is, to go beyond biological paternity and create the social role of father. Especially given the level of teaching required to get Homo sapien children able to fend for themselves.

The need for provisioning males for the raising of children gave a powerful incentive for women to adopt and follow norms regulating their sexual behaviour so as to encourage such male commitment. This is interactive. The stronger the restrictive sexual norms, the stronger male provisioning is likely to be. The weaker the restrictive sexual norms, the weaker male provisioning is likely to be. A common cross-cultural pattern is for men to be willing to use violence to enforce fidelity norms, as their social standing, including their identity as a father, is at stake. Another common cross-cultural pattern is for women expressing aggression towards another woman to cast doubt on her adherence to fidelity norms.

A very common cross-cultural pattern is for a man’s mother to be concerned with policing the behaviour of his wife (or wives). She has an obvious interest in ensuring that their children are indeed (biologically) her son’s and in the protecting the reputation of her son. Remembering that propriety is, in this context, fidelity + reputation. Or, at least, preserving the presumption of fidelity.

All known foraging societies recognise the social role of father. A small number of (farming) societies do not have the social role of father. Instead, men invest in their sister’s children. As a genetic replication strategy, given one shares less genes with a niece or a nephew than with a son or a daughter, unclehood is inferior to fatherhood — provided males can be reasonably confident about the paternity of children.

The above patterns are the result of us being the big-brain ape and so the cultural ape. We are the fattest ape, as our energy-hog brains (our brains consume about a fifth to a quarter of our calorie intake) require a certain base level of energy to function. Hence we have more fat reserves than other apes. Women’s body naturally have significantly higher fat content than men’s bodies, as women regularly support two brains (the extra energy-hog brain being supported either in their womb, or via lactation).

Our brains need time to grow after birth, due to constraints on the size of a baby head’s able to emerge through pelvis (aggravated by bipedalism requiring narrower hips for physical stability). Hence how helpless our infants are, as far more of their development is after birth. They have to be fed and then taught. We have the fattest infants in the biosphere. Being the cultural ape, we have to learn to be effective occupiers of human niches by a mixture of being taught, observation and participation.

Risk and roles

Across this lengthy process of raising Homo sapien children, risks needed to be, where possible, transferred away from the care of children. Especially as if a mother died, her young children were also likely to die. This created human sex roles—sex roles being the behavioural expression of sex—that generally involved very different patterns of acquiring subsistence by males and females, hence quite different skill patterns.

In foraging societies, men would engage in the more dangerous forms of subsistence (hunting larger animals, getting honey). Women would engage in the less dangerous forms of subsistence that you could do while minding the kids (gathering plants, hunting small, relatively immobile, animals such as lizards).

A lot of the gathered plants would require significant processing, as plants (being immobile) evolve ways to discourage consumption of their flesh. This need for more processing of plant food tended to skew calorie and nutrient contribution in foraging societies to the energy-dense, highly bio-available nutrients in the food provided by men.

Men tend to form teams, because that is how they provided for, and protected, their women and children. Women tend to form cliques, as intimate emotional connections provided support for the long haul of motherhood. One can see this pattern in almost any schoolyard.

A complication is that the more disagreeable and less neurotic girls (“tomboys”) may gravitate towards team play. The more agreeable and more neurotic boys (“sissies”) may gravitate towards cliques.

Some cultures had explicit roles for “manly” women and “womanly” men. Generally, however, a male who attempted to adopt female patterns was rejecting the risks that males were expected to shoulder. This was not a way to be respected.

Gender

Being the cultural species, Homo sapiens do not only have sex roles. We also have narratives and expectations about sex. Hence, we have gender: the cultural expression of sex. To a large degree, the categories of man and woman are socially created.

Those who are same-sex attracted, or who are tomboys or sissies, are gender-dysphoric. They are somewhat alienated from standard expectations about sex. Trans folk are sex-dysphoria. They are alienated from the sexual structuring of their bodies.

Being sex-dysphoric is likely to also imply wishing to fit into the behavioural and cultural expectations of the other sex. Being gender-dysphoric does not imply alienation from the sexual structuring of one’s own body. Conflating sex-and-gender is a great way to engage in muddy, even disastrous, thinking.

The absence of matriarchal societies

While it is certainly true that families, and even groups, can have matriarchs, no known human society has been matriarchal. The requirement of men to take on higher-risk roles in order to support the raising of biologically-expensive children has meant that authority could not be presumptively female across a society. Hence the absence of matriarchal societies. Matriarchal families and figures are, however, entirely possible.

The non-universality of patriarchy

The absence of matriarchal societies does not remotely mean that all human societies are patriarchal in any strong sense. It is entirely possible to have a human society where male and female authority co-exists. That is, authority is not presumptively male across the society, so it is somewhat gender-egalitarian. Such societies are more common within particular patterns of subsistence, though a majority of societies known to the ethnographic record have been patriarchal. For instance, around 88% of traditional societies only had male political leaders (though political leadership is not the only manifestation of authority in societies). Nevertheless, even among generally patriarchal societies, the extent and intensity of the presumption of male authority has varied greatly.

There are relatively gender-egalitarian foraging and horticultural (hoe-farming) societies. If a society does not create the social role of fatherhood, then it is also likely to be relatively gender-egalitarian, as inheritance will be female-line and the connections of men to the next generation will be via their sisters. In many societies, men treasure the sister’s son relationship — they are males of the next generation a man is unambiguously related to.

Patterns of leverage

What determines how patriarchal a society is — i.e., how strongly authority is presumptively male in the society — is the relative social leverage of men and women. Women always have the leverage of sex and fertility. Men have whatever leverage comes from not being tied to the day-to-day care of children.

Any asset in a society that cannot be effectively managed while minding children, will be a presumptively male asset. Hence, while women have been very important for the transmission of culture, men have tended to dominate the creation of culture. Cultural narratives have thus tended to predominantly reinforce and validate male concerns. Hence also women have tended to be associated with nature (given their role in reproduction and child-rearing), men with the creation of culture. Such creation of culture is often conceived as a struggle for order against the more chaotic or resistant elements of nature.

The classic assets increasing male leverage are pastoralism (i.e., animal herds) and plough farming. In such societies, the predominant productive asset will be a male asset. This has been universally true in pastoralist societies. It is usually true in plough farming societies, with a few exceptions. One exception was Pharaonic Egypt, as land was re-allocated after every Nile flood. It was effectively Pharaoh’s asset rather than an asset of village males. Another is if the society does not recognise the social relationship of fatherhood, such as the in Mosuo of China. As there is no social role of fatherhood, land is passed down matrilineally and is not a male asset. (Men still do the ploughing.)

If the main productive asset in a society is presumptively male, this makes women largely dependant on male provision. This generates patterns of presumptive male authority, though the degree to which it does so can vary widely.

In low-population-density societies where the men are likely to be away, traditions of armed women are likely to develop so as to be able to defend hearth and home. This raises the leverage (and status) of women. In steppe societies, for example, while men owned the animal herds, women owned the dwellings; the yurts or gers.

Any pattern of periodic male absence tends to increase the status of women, as women will have to manage things in the absence of men. We can see this pattern operating in steppe societies, in Celtic and Germanic Europe, in Sparta (where men lived in the barracks for much of their life), in Rome (where elite men were often away in the service of Respublica) and in medieval Latin Christendom. This is generally an elite pattern, but elites disproportionately set social norms.

These were all, to varying degrees, single-spouse societies in that even an elite man would only have one wife, and a woman one husband. (There is some evidence that the original Indo-Europeans may have operated a single-spouse marriage system.) Celtic and Germanic societies often did, however, permit concubines able to produce legally recognised children. (In Brehon law, for example, it did not matter for your family identity who your mother was, merely who your father was.)

If elite males are required to have only one wife, then that tends to raise the status of women, as the natural thing to do is to have partnership marriages (united by care for their children), with the wife (or sometimes his mother) operating as their husband’s (or son’s) deputy when he is away and helping to manage the household when he is present. This is very much not the pattern in polygynous societies where wives competed for the prospects for their children. This meant that leaving one of the wives in charge in the absence of the husband was a recipe for disaster. (If concubines able to produce legally-recognised children were permitted, this tended to weaken the effect of having only one wife: mistresses are concubines whose children have no inheritance rights.)

Single-spouse marriage societies thus tended to make women managing assets a normal part of the society, even if the main productive assets were presumptively male. This tended to raise the status of women and lessen the degree to which authority was presumptively male. Though the effect was much stronger if there were patterns of male absence. Thus Sparta (where men lived in barracks for much of their life) was noticeably less patriarchal than Athens. Rome was also noticeably less patriarchal than Athens, with Rome become less patriarchal as its empire grew, increasing the pattern of elite male absence and so wifely management of assets.

Being a patrilineal society generates at least some presumption of male authority, as family identity is via the male line. If it is also a kin-group society, that means that family identity and kin structures will be organised around related males. This tends to increase male leverage within the society and the presumption of male authority. Especially if, as was commonly the case, the fertility of women is treated as an asset of their kin-group. (Treating women’s fertility as an asset of their kin group leads to honour killings, which are ways of enforcing commitment to the kin group.) As authority and wealth is typically transferred from father to son in patriarchal societies, such societies tend to be very controlling of female sexuality.

If a society permits polyandry (notably because of resource constraints where key productive assets lose value if divided), this tends to increase the potential leverage of women and to undermine any presumption of male authority. If a society permits polygyny, that tends to undermine the social leverage of women. This is particularly so if the main productive asset is presumptively male, as then the wives of (elite) males will be competing with each other for the prospects for their children, where the favour of the (shared) husband is crucial. Clearly, that will foster a general presumption of male authority.

Though it was true that even in societies that permitted polygamy, single-spouse marriages were the dominant form of marriage, again, elite patterns tended to dominate the generation of presumptions about authority.

Hoe-farming (horticultural) societies meant women having a (much) bigger role in food production than in plough (agricultural) societies, as hoe farming can be done while minding the kids. This permits much higher levels of polygyny (as it reduces the level of provision males have to engage in to support a wife) but also makes women less dependant on male provision. Hoe societies tend to have stronger patterns of female authority than plough societies. The question of the relative level of social leverage can become a complicated one.

In societies where assets are transferred between generations, there can be something of a trade-off between between transmitting genes and transmitting wealth. The stronger the incentive to minimise division of resources among children, the more likely single-spouse marriage systems are, bringing together male investment in high paternity-confidence children and female fidelity to her spouse so as to gain increased investment in her children. If such pressure is sufficiently strong all the way up the social system, polygamy may not be permitted.

The more important investment in the human capital of children, particularly sons, is for their prospects, the more likely it is that single-spouse marriage is going to be selected for. This likely helps explains why highly patriarchal Brahmin and Confucian societies had a wife and (maybe) concubine(s) pattern more than full-blown multiple wives. Indeed, the intense investment in memorisation required to raise a Brahmin child likely explains the rise of the Indian caste (jati) system.

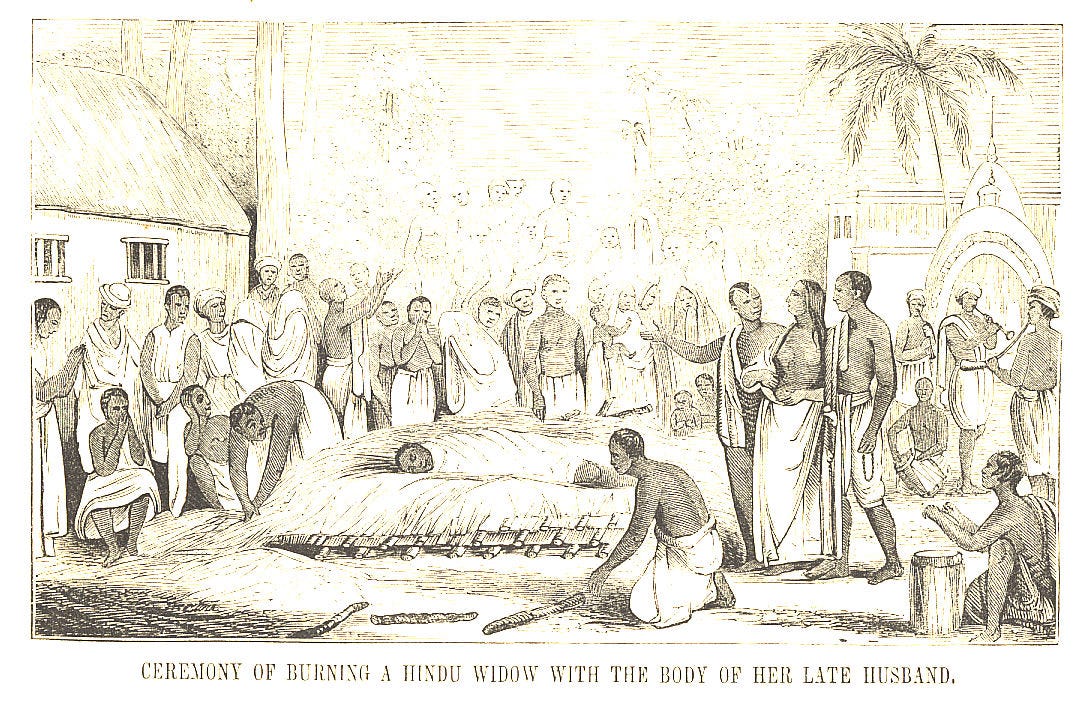

Brahmin law was particularly insistent on male authority. It was, after all, the society that valorised widows burning themselves to death on their husband’s funeral pyre.

How well members of a sex can coordinate with each other also affects social leverage. In polygynous, patrilineal, kin-group, plough-farming societies the ability of women, particularly elite women, to coordinate with each other was often very limited. Conversely, it has tended to be very easy for men in such societies to coordinate with each other, especially if male-only cults develop. Such cults are very common across human societies. Greater male coordination tends to increase male social leverage.

Increases in population density, without a commensurate increase in applied technology, tend to reduce the status of women. As population density increases, there is likely to be less male absence, discouraging the arming of women and reducing the level of women’s management of resources. There is also likely to be more pressure on social niches, encouraging more rigid delineation of sex roles. England was significantly more patriarchal in the C18th than it had been in Saxon times, around a millennium earlier.

Precisely because social leverage matters, history is not simply a pattern of upward improvement in the status of women, but of shifts back and forth.

Raiding and warfare

How raiding and warfare operates in a society also affects social leverage. If raiding and warfare is sufficiently endemic, that generates a premium on male cooperation. That tends to favour patrilineal kin systems, as related males who have grown up together are likely to be more effective in combat operations.

In small-scale societies, especially patrilineal ones where women marry away from their natal kin, endemic raiding and warfare particularly tends to generate male cults as it is important for the men to be able to coordinate planned raids and attack without women warning their relatives. Such male cults often enforce their privacy through ferocious punishments. That increases male social leverage, generating a presumption of male authority and providing a social mechanism to establish and reinforce male authority.

Endemic warfare and raiding can, however, encourage single-spouse marriage systems. Polygyny means that some men are cut out of the local marriage market. If circumstances are such that a premium is put on local social cohesion, then single-spouse marriage systems can be selected for so as to maximise the number of local males with a commitment to the local social order via having their own wife and children. (Note, this does not imply that reducing reproductive variance among men is what is being selected for.) Such pressure for single-spouse marriage for greater social cohesion can also apply to minority religious groups, such as the Alevis.

Shifting social leverage

What is hopefully clear from the above is that patriarchy is not some nefarious male plot. It is a social phenomena driven by the relative social leverage of men and women in a society. The level of patriarchy can thus vary widely between societies. It can also vary in the same society across time, if the underlying social constraints change in ways that shift the leverage between men and women.

That the Christian Church sanctified single-spouse marriage (including no concubines), insisted on the importance of legitimacy (making it very important who your mother was and whether she was married to your father), insisted on female consent being required for marriage, strongly supported female testamentary rights (and the property rights entailed therein) and, in conjunction with manorialism, broke up kin groups, meant that the status of women was significantly higher in Christian Europe than was the case in Islam, Brahmin India or Confucian East Asia. As I have noted previously, feminism was only likely to arise within Latin Christendom-cum-Western civilisation.

Technological change since the emergence of mass-prosperity societies, starting with the development of railways and steamships in the 1820s, has tended to further increase the status of women. The increase in the number of low-physical-risk jobs, the development of domestic technology (reducing the time-and-physical-skill-burden of managing a household), and the development of mass education (reducing the time-and-attention burden of raising kids), as well as shrinking family sizes, have all greatly increased the capacity of women to earn income outside the home. The fall in transport and communication costs has also made it easier for women to coordinate and organise.

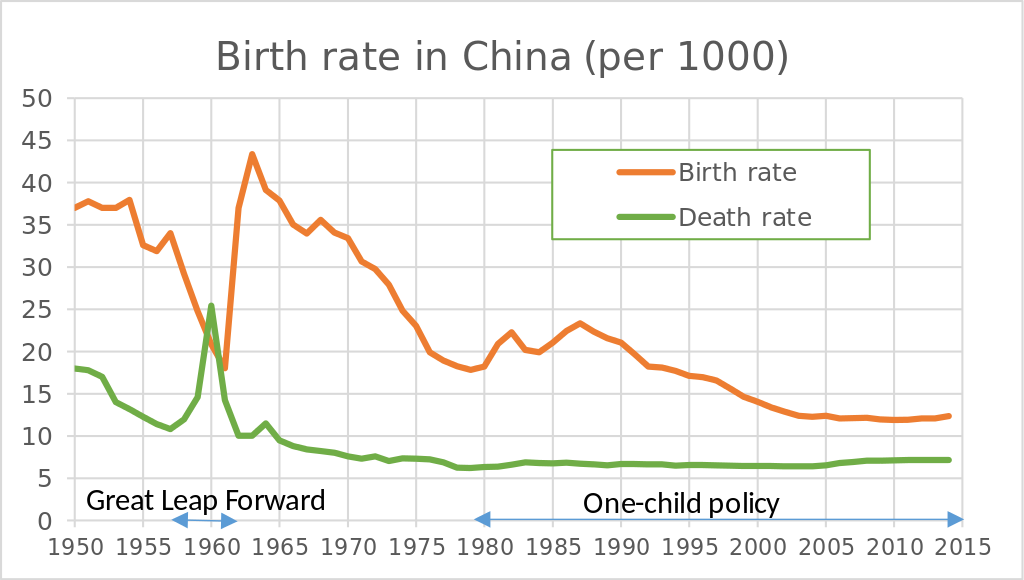

The most dramatic change, however, has been the legal and technological changes that have given women unilateral control over their fertility. This has decoupled sex and marriage, a huge social shift in itself. But it also meant that women have been able to invest in higher education, greatly increasing their employment as professionals, managers and other high-status jobs. These changes have also greatly increased women’s role in the creation of culture.

Hence we now have the first societies in human history increasingly without presumptive sex roles. This is a dramatic cultural and evolutionary novelty. Needless to say, gender expectations and narratives have been in considerable flux.

These changes also mean that men and women have fairly similar levels of social leverage. As biologist Bobbi S. Low notes:

Children

Homo sapiens are mammals. Female mammals have mammary glands so that when the child emerges, their immediate food source is on-tap.

In most mammal species, that means the male plays no role in raising children, as the female is already committed (via the mammary glands) to feeding the children. This is the cad strategy for reproduction. The more the children have to be taught how to feed, and the longer they have to be fed before they can feed themselves, the more likely some male involvement in the feeding of the offspring is (the dad strategy).

Male provision is not to be confused with mate-guarding. Mate-guarding is about taking possession of the fertility of a female for one’s own use, excluding other males. It implies nothing regarding the care of children. Most mate-guarding mammal species have cad-strategy males. They are just possessive cads.

In contemporary foraging societies, on average, children do not “break even” in producing and consuming calories until about the age of 20. So, a Homo sapien child, on average, has likely represented about a 20 year-feeding-protection-and-instruction investment. This was not possible without provisioning males.

In contemporary foraging societies, men provide a majority of calories to the group, an overwhelming majority of the protein to the group and almost completely dominate provision of calories and protein consumed by post-weaning children. The only evolutionary stable way to get males to invest that much effort in provisioning children is having them feed the children that are presumptively theirs. That is, to go beyond biological paternity and create the social role of father. Especially given the level of teaching required to get Homo sapien children able to fend for themselves.

The need for provisioning males for the raising of children gave a powerful incentive for women to adopt and follow norms regulating their sexual behaviour so as to encourage such male commitment. This is interactive. The stronger the restrictive sexual norms, the stronger male provisioning is likely to be. The weaker the restrictive sexual norms, the weaker male provisioning is likely to be. A common cross-cultural pattern is for men to be willing to use violence to enforce fidelity norms, as their social standing, including their identity as a father, is at stake. Another common cross-cultural pattern is for women expressing aggression towards another woman to cast doubt on her adherence to fidelity norms.

A very common cross-cultural pattern is for a man’s mother to be concerned with policing the behaviour of his wife (or wives). She has an obvious interest in ensuring that their children are indeed (biologically) her son’s and in the protecting the reputation of her son. Remembering that propriety is, in this context, fidelity + reputation. Or, at least, preserving the presumption of fidelity.

All known foraging societies recognise the social role of father. A small number of (farming) societies do not have the social role of father. Instead, men invest in their sister’s children. As a genetic replication strategy, given one shares less genes with a niece or a nephew than with a son or a daughter, unclehood is inferior to fatherhood — provided males can be reasonably confident about the paternity of children.

The above patterns are the result of us being the big-brain ape and so the cultural ape. We are the fattest ape, as our energy-hog brains (our brains consume about a fifth to a quarter of our calorie intake) require a certain base level of energy to function. Hence we have more fat reserves than other apes. Women’s body naturally have significantly higher fat content than men’s bodies, as women regularly support two brains (the extra energy-hog brain being supported either in their womb, or via lactation).

Our brains need time to grow after birth, due to constraints on the size of a baby head’s able to emerge through pelvis (aggravated by bipedalism requiring narrower hips for physical stability). Hence how helpless our infants are, as far more of their development is after birth. They have to be fed and then taught. We have the fattest infants in the biosphere. Being the cultural ape, we have to learn to be effective occupiers of human niches by a mixture of being taught, observation and participation.

Risk and roles

Across this lengthy process of raising Homo sapien children, risks needed to be, where possible, transferred away from the care of children. Especially as if a mother died, her young children were also likely to die. This created human sex roles—sex roles being the behavioural expression of sex—that generally involved very different patterns of acquiring subsistence by males and females, hence quite different skill patterns.

In foraging societies, men would engage in the more dangerous forms of subsistence (hunting larger animals, getting honey). Women would engage in the less dangerous forms of subsistence that you could do while minding the kids (gathering plants, hunting small, relatively immobile, animals such as lizards).

A lot of the gathered plants would require significant processing, as plants (being immobile) evolve ways to discourage consumption of their flesh. This need for more processing of plant food tended to skew calorie and nutrient contribution in foraging societies to the energy-dense, highly bio-available nutrients in the food provided by men.

Men tend to form teams, because that is how they provided for, and protected, their women and children. Women tend to form cliques, as intimate emotional connections provided support for the long haul of motherhood. One can see this pattern in almost any schoolyard.

A complication is that the more disagreeable and less neurotic girls (“tomboys”) may gravitate towards team play. The more agreeable and more neurotic boys (“sissies”) may gravitate towards cliques.

Some cultures had explicit roles for “manly” women and “womanly” men. Generally, however, a male who attempted to adopt female patterns was rejecting the risks that males were expected to shoulder. This was not a way to be respected.

Gender

Being the cultural species, Homo sapiens do not only have sex roles. We also have narratives and expectations about sex. Hence, we have gender: the cultural expression of sex. To a large degree, the categories of man and woman are socially created.

Those who are same-sex attracted, or who are tomboys or sissies, are gender-dysphoric. They are somewhat alienated from standard expectations about sex. Trans folk are sex-dysphoria. They are alienated from the sexual structuring of their bodies.

Being sex-dysphoric is likely to also imply wishing to fit into the behavioural and cultural expectations of the other sex. Being gender-dysphoric does not imply alienation from the sexual structuring of one’s own body. Conflating sex-and-gender is a great way to engage in muddy, even disastrous, thinking.

The absence of matriarchal societies

While it is certainly true that families, and even groups, can have matriarchs, no known human society has been matriarchal. The requirement of men to take on higher-risk roles in order to support the raising of biologically-expensive children has meant that authority could not be presumptively female across a society. Hence the absence of matriarchal societies. Matriarchal families and figures are, however, entirely possible.

The non-universality of patriarchy

The absence of matriarchal societies does not remotely mean that all human societies are patriarchal in any strong sense. It is entirely possible to have a human society where male and female authority co-exists. That is, authority is not presumptively male across the society, so it is somewhat gender-egalitarian. Such societies are more common within particular patterns of subsistence, though a majority of societies known to the ethnographic record have been patriarchal. For instance, around 88% of traditional societies only had male political leaders (though political leadership is not the only manifestation of authority in societies). Nevertheless, even among generally patriarchal societies, the extent and intensity of the presumption of male authority has varied greatly.

There are relatively gender-egalitarian foraging and horticultural (hoe-farming) societies. If a society does not create the social role of fatherhood, then it is also likely to be relatively gender-egalitarian, as inheritance will be female-line and the connections of men to the next generation will be via their sisters. In many societies, men treasure the sister’s son relationship — they are males of the next generation a man is unambiguously related to.

Patterns of leverage

What determines how patriarchal a society is — i.e., how strongly authority is presumptively male in the society — is the relative social leverage of men and women. Women always have the leverage of sex and fertility. Men have whatever leverage comes from not being tied to the day-to-day care of children.

Any asset in a society that cannot be effectively managed while minding children, will be a presumptively male asset. Hence, while women have been very important for the transmission of culture, men have tended to dominate the creation of culture. Cultural narratives have thus tended to predominantly reinforce and validate male concerns. Hence also women have tended to be associated with nature (given their role in reproduction and child-rearing), men with the creation of culture. Such creation of culture is often conceived as a struggle for order against the more chaotic or resistant elements of nature.

The classic assets increasing male leverage are pastoralism (i.e., animal herds) and plough farming. In such societies, the predominant productive asset will be a male asset. This has been universally true in pastoralist societies. It is usually true in plough farming societies, with a few exceptions. One exception was Pharaonic Egypt, as land was re-allocated after every Nile flood. It was effectively Pharaoh’s asset rather than an asset of village males. Another is if the society does not recognise the social relationship of fatherhood, such as the in Mosuo of China. As there is no social role of fatherhood, land is passed down matrilineally and is not a male asset. (Men still do the ploughing.)

If the main productive asset in a society is presumptively male, this makes women largely dependant on male provision. This generates patterns of presumptive male authority, though the degree to which it does so can vary widely.

In low-population-density societies where the men are likely to be away, traditions of armed women are likely to develop so as to be able to defend hearth and home. This raises the leverage (and status) of women. In steppe societies, for example, while men owned the animal herds, women owned the dwellings; the yurts or gers.

Any pattern of periodic male absence tends to increase the status of women, as women will have to manage things in the absence of men. We can see this pattern operating in steppe societies, in Celtic and Germanic Europe, in Sparta (where men lived in the barracks for much of their life), in Rome (where elite men were often away in the service of Respublica) and in medieval Latin Christendom. This is generally an elite pattern, but elites disproportionately set social norms.

These were all, to varying degrees, single-spouse societies in that even an elite man would only have one wife, and a woman one husband. (There is some evidence that the original Indo-Europeans may have operated a single-spouse marriage system.) Celtic and Germanic societies often did, however, permit concubines able to produce legally recognised children. (In Brehon law, for example, it did not matter for your family identity who your mother was, merely who your father was.)

If elite males are required to have only one wife, then that tends to raise the status of women, as the natural thing to do is to have partnership marriages (united by care for their children), with the wife (or sometimes his mother) operating as their husband’s (or son’s) deputy when he is away and helping to manage the household when he is present. This is very much not the pattern in polygynous societies where wives competed for the prospects for their children. This meant that leaving one of the wives in charge in the absence of the husband was a recipe for disaster. (If concubines able to produce legally-recognised children were permitted, this tended to weaken the effect of having only one wife: mistresses are concubines whose children have no inheritance rights.)

Single-spouse marriage societies thus tended to make women managing assets a normal part of the society, even if the main productive assets were presumptively male. This tended to raise the status of women and lessen the degree to which authority was presumptively male. Though the effect was much stronger if there were patterns of male absence. Thus Sparta (where men lived in barracks for much of their life) was noticeably less patriarchal than Athens. Rome was also noticeably less patriarchal than Athens, with Rome become less patriarchal as its empire grew, increasing the pattern of elite male absence and so wifely management of assets.

Being a patrilineal society generates at least some presumption of male authority, as family identity is via the male line. If it is also a kin-group society, that means that family identity and kin structures will be organised around related males. This tends to increase male leverage within the society and the presumption of male authority. Especially if, as was commonly the case, the fertility of women is treated as an asset of their kin-group. (Treating women’s fertility as an asset of their kin group leads to honour killings, which are ways of enforcing commitment to the kin group.) As authority and wealth is typically transferred from father to son in patriarchal societies, such societies tend to be very controlling of female sexuality.

If a society permits polyandry (notably because of resource constraints where key productive assets lose value if divided), this tends to increase the potential leverage of women and to undermine any presumption of male authority. If a society permits polygyny, that tends to undermine the social leverage of women. This is particularly so if the main productive asset is presumptively male, as then the wives of (elite) males will be competing with each other for the prospects for their children, where the favour of the (shared) husband is crucial. Clearly, that will foster a general presumption of male authority.

Though it was true that even in societies that permitted polygamy, single-spouse marriages were the dominant form of marriage, again, elite patterns tended to dominate the generation of presumptions about authority.

Hoe-farming (horticultural) societies meant women having a (much) bigger role in food production than in plough (agricultural) societies, as hoe farming can be done while minding the kids. This permits much higher levels of polygyny (as it reduces the level of provision males have to engage in to support a wife) but also makes women less dependant on male provision. Hoe societies tend to have stronger patterns of female authority than plough societies. The question of the relative level of social leverage can become a complicated one.

In societies where assets are transferred between generations, there can be something of a trade-off between between transmitting genes and transmitting wealth. The stronger the incentive to minimise division of resources among children, the more likely single-spouse marriage systems are, bringing together male investment in high paternity-confidence children and female fidelity to her spouse so as to gain increased investment in her children. If such pressure is sufficiently strong all the way up the social system, polygamy may not be permitted.

The more important investment in the human capital of children, particularly sons, is for their prospects, the more likely it is that single-spouse marriage is going to be selected for. This likely helps explains why highly patriarchal Brahmin and Confucian societies had a wife and (maybe) concubine(s) pattern more than full-blown multiple wives. Indeed, the intense investment in memorisation required to raise a Brahmin child likely explains the rise of the Indian caste (jati) system.

Brahmin law was particularly insistent on male authority. It was, after all, the society that valorised widows burning themselves to death on their husband’s funeral pyre.

How well members of a sex can coordinate with each other also affects social leverage. In polygynous, patrilineal, kin-group, plough-farming societies the ability of women, particularly elite women, to coordinate with each other was often very limited. Conversely, it has tended to be very easy for men in such societies to coordinate with each other, especially if male-only cults develop. Such cults are very common across human societies. Greater male coordination tends to increase male social leverage.

Increases in population density, without a commensurate increase in applied technology, tend to reduce the status of women. As population density increases, there is likely to be less male absence, discouraging the arming of women and reducing the level of women’s management of resources. There is also likely to be more pressure on social niches, encouraging more rigid delineation of sex roles. England was significantly more patriarchal in the C18th than it had been in Saxon times, around a millennium earlier.

Precisely because social leverage matters, history is not simply a pattern of upward improvement in the status of women, but of shifts back and forth.

Raiding and warfare

How raiding and warfare operates in a society also affects social leverage. If raiding and warfare is sufficiently endemic, that generates a premium on male cooperation. That tends to favour patrilineal kin systems, as related males who have grown up together are likely to be more effective in combat operations.

In small-scale societies, especially patrilineal ones where women marry away from their natal kin, endemic raiding and warfare particularly tends to generate male cults as it is important for the men to be able to coordinate planned raids and attack without women warning their relatives. Such male cults often enforce their privacy through ferocious punishments. That increases male social leverage, generating a presumption of male authority and providing a social mechanism to establish and reinforce male authority.

Endemic warfare and raiding can, however, encourage single-spouse marriage systems. Polygyny means that some men are cut out of the local marriage market. If circumstances are such that a premium is put on local social cohesion, then single-spouse marriage systems can be selected for so as to maximise the number of local males with a commitment to the local social order via having their own wife and children. (Note, this does not imply that reducing reproductive variance among men is what is being selected for.) Such pressure for single-spouse marriage for greater social cohesion can also apply to minority religious groups, such as the Alevis.

Shifting social leverage

What is hopefully clear from the above is that patriarchy is not some nefarious male plot. It is a social phenomena driven by the relative social leverage of men and women in a society. The level of patriarchy can thus vary widely between societies. It can also vary in the same society across time, if the underlying social constraints change in ways that shift the leverage between men and women.

That the Christian Church sanctified single-spouse marriage (including no concubines), insisted on the importance of legitimacy (making it very important who your mother was and whether she was married to your father), insisted on female consent being required for marriage, strongly supported female testamentary rights (and the property rights entailed therein) and, in conjunction with manorialism, broke up kin groups, meant that the status of women was significantly higher in Christian Europe than was the case in Islam, Brahmin India or Confucian East Asia. As I have noted previously, feminism was only likely to arise within Latin Christendom-cum-Western civilisation.

Technological change since the emergence of mass-prosperity societies, starting with the development of railways and steamships in the 1820s, has tended to further increase the status of women. The increase in the number of low-physical-risk jobs, the development of domestic technology (reducing the time-and-physical-skill-burden of managing a household), and the development of mass education (reducing the time-and-attention burden of raising kids), as well as shrinking family sizes, have all greatly increased the capacity of women to earn income outside the home. The fall in transport and communication costs has also made it easier for women to coordinate and organise.

The most dramatic change, however, has been the legal and technological changes that have given women unilateral control over their fertility. This has decoupled sex and marriage, a huge social shift in itself. But it also meant that women have been able to invest in higher education, greatly increasing their employment as professionals, managers and other high-status jobs. These changes have also greatly increased women’s role in the creation of culture.

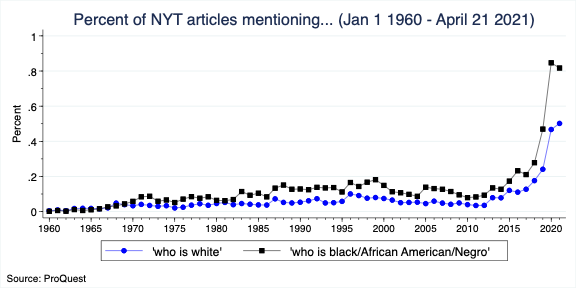

Hence we now have the first societies in human history increasingly without presumptive sex roles. This is a dramatic cultural and evolutionary novelty. Needless to say, gender expectations and narratives have been in considerable flux.

These changes also mean that men and women have fairly similar levels of social leverage. As biologist Bobbi S. Low notes:

...men’s value to women is no longer solely or primarily resource value, and women’s value to men is no longer solely or primarily reproductive value.Women still have the leverage of sex and fertility, but that is strongly age-dependent, is somewhat weakened by the relative availability of sexual outlets and the undermining of the status and value (and so the appeal) of fatherhood.

The presumption of greater maternal involvement in child-raising is a universal human cultural pattern that, while it shows variations among cultures, is substantially driven by biology. It is not a manifestation of patriarchy. Due to the biological processes of pregnancy and lactation, cultural conceptions of motherhood, while they do vary, vary much less than do cultural conceptions of fatherhood, which (unlike biological paternity) is a socially created role.

Apart from some rapidly fading cultural traces, contemporary Western societies do not face the problems of patriarchy. Instead, developed societies face the problems of dealing with a dramatic level of evolutionary novelty. Such as the dramatic fading of presumptive sex roles.

Beating the patriarchy drum may be emotionally satisfying, and have some residual propaganda value, but it is mostly just a giant, self-indulgent, distraction from working through the continuing implications of these dramatic changes and the sea of evolutionary novelty we find ourselves in.

[Cross-posted, somewhat improved, from Medium.]